Away back in those “unstructured” days before boys were given all-terrain, all-wheel-drive, motor vehicles almost as soon as they could walk, the standard gift for being “a good boy (whatever that meant) was a coaster wagon.

Although coaster wagons are still with us in greatly reduced numbers and under other names, it may be necessary to define what was meant by a coaster wagon in 1924. It had a wooden box, four wheels, two of which could be steered and a tongue by which it could be pulled. By name, coaster wagons were usually “auto wheel coasters”, “disco flyers” or “fairy soap wagons”. The names, of course, did not describe the wagons. The “auto wheel coaster” had steel-shod wheels and therefore was not like an automobile. The “Disco Flyer” had rubber-tired disc wheels and did not fly because the rubber tires stuck to the pavement. Moreover, although the name “disco” was used you could not dance in it. The “fairy soap wagon” did not promote cleanliness among fairy-tale people, as the name implied, but rather encouraged people to use the soap manufactured by the Fairy Soap Company.

Why the name “coaster”? The dictionary defines the word as meaning a small ship that trades along the coast. The verb “to coast” means to slide down a hill on a sled or to run down a hill on a bicycle with your feet off the pedals. None of these descriptions applied to the coaster wagon or the effort required to propel it.

Coaster wagons were propelled by the feet with a method described as “pumping”. This was a widely us word that was also used to describe the propulsion of a swing or a bicycle. Actually the word “pumping” has nothing to do with any of these activities. The noun “pump” means a type of snow or a device to raise water, oil, or air pressure. The verb “to pump” means to pry information from someone, to shake hands, to inflate tires, to be out of breath, or (of all things) to urinate. None of these definitions applied to “pumping” a coaster wagon and kids flew along King Street in 1924 quite oblivious of the fact that what they were doing had nothing to do with pumps or pumping.

‘Pumping” a coaster wagon was an art. Boys maintained that speed could only be obtained if the non-pumping foot was over the end of the wagon box and it was claimed that girls could never achieve speed in a coaster wagon because they kept their non-pumping foot inside the box and in the macho days of 1924 any boy who pumped his wagon with his foot in the box was regarded with suspicion. “Pump-in” a roaster was not without some risk for the wheels were attached to the bare axle-end with a split pin and consequently when a boy was “pumping” hard his ankle was apt to strike the axle end and a nasty scrape would result. However, it was a point of honour never to cry “ouch” or to let on that anything had happened. After all our heroes in “The Youth’s Companion”, “Chums” or “The American Boy” magazines never flinched when their limbs were blown off, sawed off, chewed off, pulled off or shot off so why should their imitators let on that they had sustained an injury? Kids kept a stiff upper lip until they got home where they would prophesy that they would never walk again unless they received an immediate application of witch hazel.

Sometimes the coaster wagon was described as an “express wagon” as the word “express” was used in 1924 to describe speed and railway travel. In the days before jet aircraft, trips to the moon and Friday night traffic in Bur-ford, a kid’s idea of speed and daring was to fly an aeroplane or to drive an “express” locomotive. Since aeroplanes seldom visited Burford, kids had to be content with the role of “the brave engineer” who drove trains at 60 miles per hour and when involved in an accident was always found “with his hand on the throttle” presumably trying to get more speed out of his engine. Railroad engineers were the 1924 criterion for heroic daring and thus kids accepted the name “express wagon” as a vehicle capable of speeds almost equal to that attained by the four “express” passenger trains that passed through Burford every day.

So what was so big about the coaster wagon? By 1987 standards of childhood entertainment it would rate very low as a totally unsophisticated plaything. It does not have computers, computer chips, software, microfiche sheets or word processors. It did not convert to a person-eating monster or an interstellar rocket by the touch of a switch. It did not sing, make print-outs, or tell people to “have a good day”. It did not have expensive batteries to go dead nor did it have preprinted electronic circuits. It did not present “a structured program of pre-teen modality or activity.” It was not “a personally motivated, recreationalized device for inter-sexual relationship between post-infancy peer groupings.” No, it was just a simple toy that parents gave to their children with the unspoken wish, “There it is. Make the most of it and keep out of the way.”

Any comparison between the 1924 coaster wagon and the high-tech toys of 1987 is bound to create a laugh but we must remember that in 1924 there was no TV and little radio to entertain children when school was out. There were no organized snorts or recreational programs. Motor cars were not available, at a moment’s notice, to take

children to places of entertainment. Few homes had labour-saving devices or even ice boxes,and while it was not unusual for Bur-ford families to have “hired girls”, parents were required to undertake much hard, sweaty, labour in order to keep things going. Most children were left to organize their own entertainment with few accessories other than their own imagination. Imagination played a great part in the fives of the 1924 child and this imagination was based on stories children read in their Sunday School papers, the weekly “funny papers”, or for the more fortunate child in such magazines as “The Youth’s Companion”, “Chums”, “St. Nicholas” or “The American Boy”.

The coaster wagon was an ideal vehicle with which to exercise the imagination. If there was a circus in Brantford with a parade, you could be sure that in a few days a “circus parade” of coaster wagons would appear in Bur-Ford with docile and bewildered dogs looking from cardboard boxes unaware that they were really tigers and lions. If two coaster wagons were hitched together they became the Burford “express” stopping at every crossing. If they were upside down they became Grey-Dort limousines being repaired at Billy Mclnally’s garage. If the owners had cap guns, coaster wagons became black Hudson touring cars whose occupants were the Burford Bootleggers speeding to Detroit. IT there were cardboard boxes big enough to hold kids the wagons were settlers’ covered wagons heading west. If the cardboard boxes had holes in the side and the occupants had cap-guns, the wagons were tanks going into action on the Western Front. Sometimes imagination turned to Biblical scenes from Sunday School and on one occasion coaster wagons were turned upside down by a mud puddle where kids, by turning the wheels and thrusting mud and grass between the spokes, imagined that they were Israelites in Egypt turning straw into bricks. When everyone’s imagination failed to produce a new scene, the wagons would be hauled under a tree to serve as a spot for serious conversation and boasting – “My aunt plays the slide trombone, “My uncle knows an elephant”, “My Dad can lick your Dad”, etc., etc. On rare occasions imagination was replaced by reality and I can recall an occasion when three coaster wagons were fastened together so that a raft could be transported to the creek one mile north of Burford.

Ownership of a coaster wagon had some disadvantages’ one of which was the fact that certain little girls felt that they had the right to sit in wagons and nave little boys haul them all over town, day in and day out. The more precocious boys obliged them but the shy boys. either ran off or yelled “Haw Haw”. It doesn’t say much f9r interpersonal relationships to relate that the way this tedious task was terminated was to pull the wagon as fast as possible towards the girl’s front lawn where by a sudden stop and turn the persistent passenger could be tossed out on the grass and left to bemoan her fate with howls of rage.

Most of the frivolity of coaster wagon days has long since departed from the local scene with one exception – In 1924 kids who had coaster wagons knew the location of every crack or hole in the sidewalks that might impede their progress. It is interesting to note that many of these cracks and holes still exist over 60 years later. However, in 1987 when most kids of “coaster wagon” age play among the 24-wheeler traffic on ten-speed bicycles I don’t imagine anyone cares about such trivial things as holes in the sidewalk.

Looking back at the “coaster wagon” days of more than 60 years ago I neither praise nor condemn them. They were part of a different time and represented different attitudes and thus must stand on their own. However, having said that, an obvious comparison seems to be necessary In 1924 when children were left on their own they developed independent initiative by using what few resources were available to them. Now when high-tech devices rule the lives of children, it is sad to hear them say “I’m bored, There’s nothing to do” whenever their batteries go dead.

– ‘Coaster wagons were a child’s entertainment back in 1924 era’ by Mel Robertson, The Burford Times, 22 July, 1987

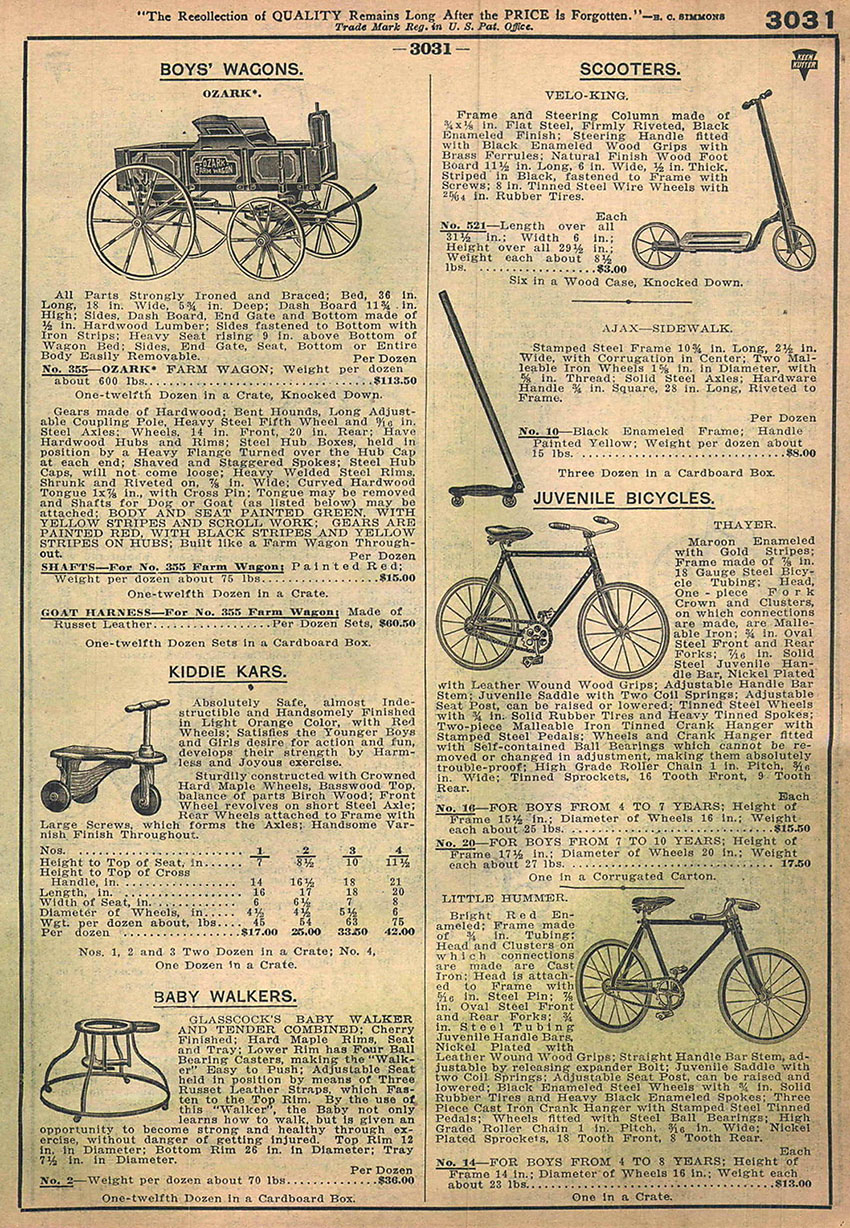

The Hummer company started in 1851 as the Post Implement Co, making ploughs. Sattley Bros purchased the company around 1875, expanding it to make a larger range of agricultural machinery. It merged with the Racing Buggy Co of Racine, Wisconsin in 1910, and then became the Hummer Plow Works after being purchased by Montgomery Ward in 1916. Between 1916 and 1937, the factory manufactured a wide range of products including a complete line of horse drawn tillage tools, washing machines, coaster wagons, kids bikes, folding camp beds, windmills, poultry equipment, air compressors, bottle cappers, gasoline engines, cream separators, water supply systems and hammer mills. The ‘Hummer’ name was best known for its engines. But, of course, nowadays, a ‘Hummer’ is only known as the largest American vehicle available for public purchase. It was derived from the US Army’s M998 Humvee – the High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicle – which became the ‘star’ of the 1st Gulf War’s ‘Desert Storm’ beamed live on TV into millions of American homes.

The contrast could not be greater between the modern Hummer and its early 20th century ancestor!

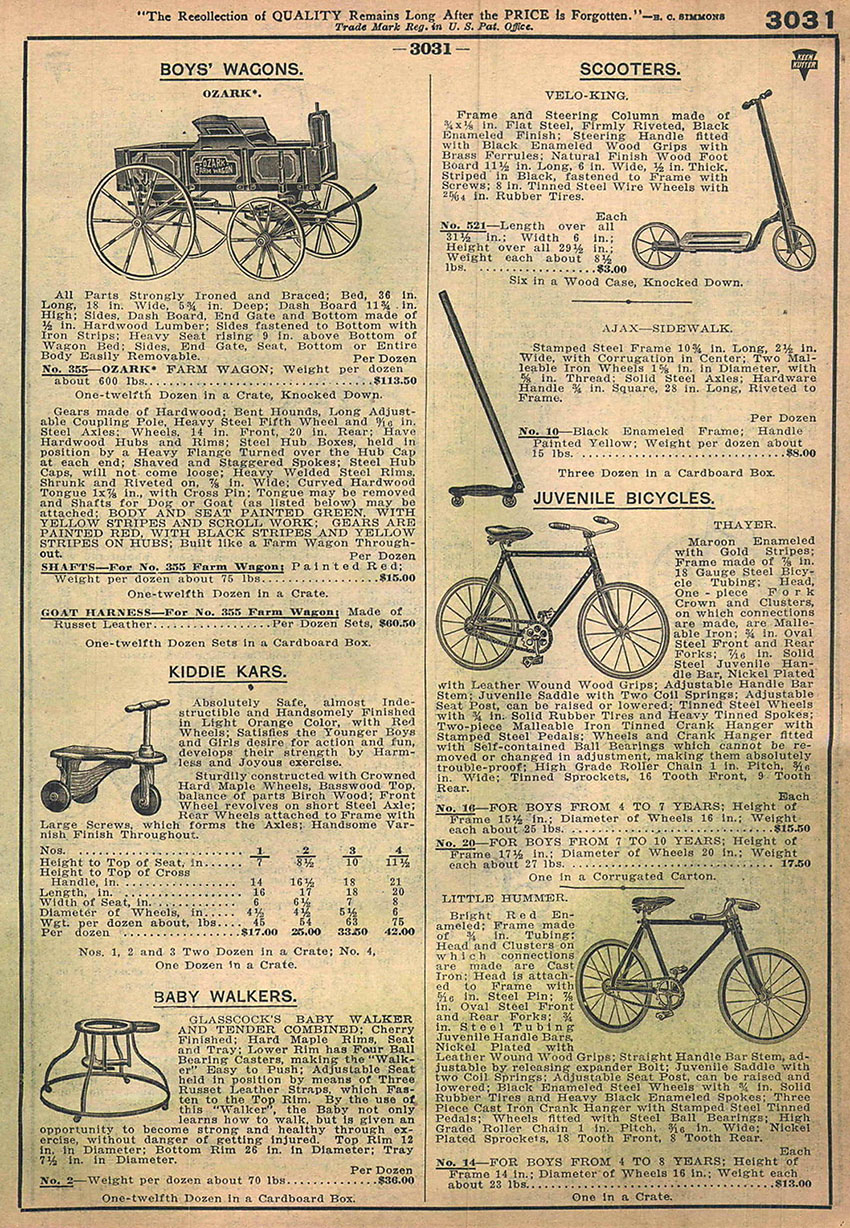

1890s-1910s Hummer Wagon

Body Length: 20″

Body Width: 12″

The first children’s transportation toys were miniature versions of adult farm wagons. Early models were pulled or pushed, developing into ‘coaster’ wagons after it was observed that children liked to sit inside them to roll downhill. Early examples were made entirely of wood. The wheels had wooden hubs, spokes and rims with steel band ‘tyres.’ Rear wheels were larger than the front. Gendron and other manufacturers soon started making metal wagons, which were more robust, and metal wagons became the dominant style in the 1930s. After WW2, wagon design evolved further: in the simplest form they became trailers to be pulled behind pedal cars, particularly tractors. A few manufacturers also made ‘pedal wagons’ which were velocipede tricycles with an open box behind the seat. And, as adult size wagons evolved into trucks, pedal car trucks were therefore another evolutionary stage of the early coaster and pull wagon.

It’s not easy to calculate the age of early wooden wagons: the illustration (above) of a similar wagon is from the 1895 Montgomery Ward catalogue; both painted and unpainted versions were on offer. Montgomery Ward’s purchase of the company that made Hummer farm equipment in 1916 could mean that they called some of their wagons ‘Hummer.’ I’ve just ordered Gordon Westover’s new toy wagon book ‘Coasting on Wheels’ so I hope I’ll have some extra information to update this page after I receive it.

What makes it hard to date this particular example is its condition. It was discovered in the loft of a Civil War era mansion in Keyport, New Jersey, USA, seven years ago. It was still in its box, not assembled. The box had dried out with age, but the wagon itself is in as-new condition. As you can see, it is of very simple construction, and is complete except for end caps to hold on the wheels.

I bought it from Walt, who found it when he was contracted to clear the mansion, prior to the construction of a new golf course. The house, being of historic interest, was moved across the road. Walt and his wife kept the Hummer on display in their lounge (below) until selling it to me.

1895 MONTGOMERY WARD CATALOGUE

1917 SIMMONS ‘LITTLE HUMMER’ BICYCLE

FOOTNOTE

It appears that Matthew Harrison didn’t know about the Hummer’s wooden ancestor before creating his piece of art pictured above, in 2008:

No, people haven’t lost their mind with the widespread economic turmoil -well, not yet at least- as this Hummer H3 that’s fitted with a set of wooden wagon wheels is actually a piece of art created by Matthew Harrison and it’s on show at the fifth Zoo Art Fair (17-20 October) in central London. Harrison said that he combined the Hummer’s off-road credentials with ‘Wild West’ wooden wheels to create ‘a sculpture that is a mixture of art, engineering and motoring.’

1987 Mel Robinson coaster wagon article with thanks to – http://images.ourontario.ca/brant/2350281/data

Hummer Mfg Co info with thanks to – http://www.gasenginemagazine.com/tractors/interesting-notes.aspx

Wild West Hummer with thanks to – http://www.carscoops.com/2008/10/hummer-h3-on-wooden-stilts-all-in-name.html

Matthew Harrison – https://www.shu.ac.uk/research/c3ri/people/matthew-harrison