There can not be any question as to the value cyclists from this colony would be in scouting and dispatch work. One cannot help thinking that given the opportunity, some of our ‘special’ riders and overlanders would perform work which would come as a revelation to even those who believe in the utility of the cycle in (dispatch) service. From England, wheelmen are being sent out attached to several corps, but to Australians it is somewhat amusing to read that their machines are of the heavy roadster type, and are fitted with mudguards and brakes. A hundred of such cyclists would not be as valuable as half a dozen of the pioneer wheelmen of Australia.

– The Bicycle in Wartime, page 68, by Jim Fitzpatrick, quoting Percy Armstrong, ‘Cyclists for the Transvaal,’ The Western Mail, Feb 17, 1900, pp 18-19

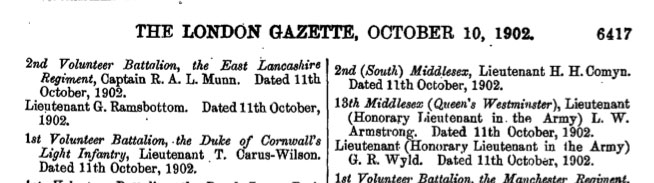

Alldays & Onions Ltd was the first company to secure large contracts with the British Government to supply military bicycles for the Boer War. A military pattern machine had not yet been established by the War Office; this was to follow in 1901, with the ‘Bicycle (Mark 1) High. Medium. Low.’

So it’s interesting to compare this earlier military machine, which was, by comparison, very basic, with the later heavy duty machines.

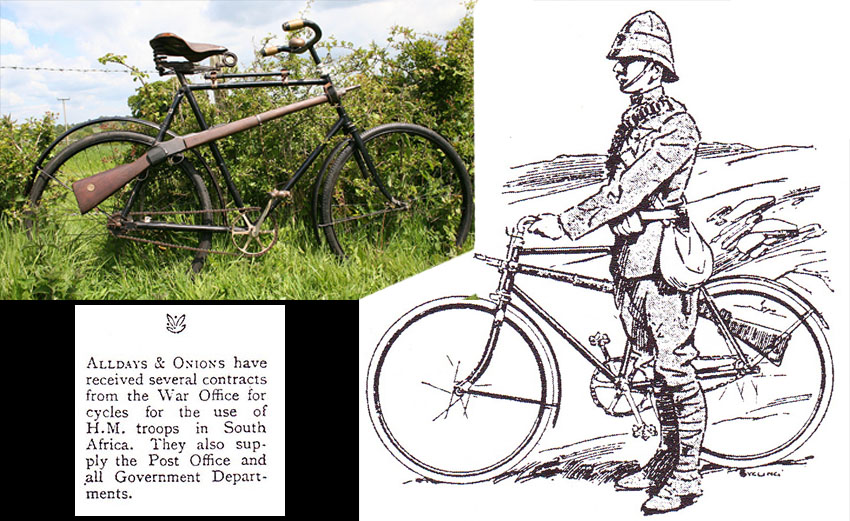

The military pattern Alldays Matchless illustrated above shows a fixed wheel bicycle with front plunger brake. This example is fitted with a coaster brake. The freewheel and coaster brake was introduced in 1897 and put onto the market for the first time for the 1898 season. With the advent of the coaster brake, rear carrier racks were subsequently patented too, H.G Turner’s being either the first or one of the first, in 1899. Previously, on fixed wheel machines, rear carriers could not be used …for the simple reason that jumping off the back of the bicycle was the safest route should a rider need an ’emergency exit.’ The step fitted to the near side of the rear axle of a fixed wheel bicycle was also the means by which a rider would mount a bicycle, particularly if the bicycle was too tall for him to mount from the pedals.

Obviously, bicycles supplied in bulk through a government contract were not tailored to size requirements of individual riders, and machines in this era were invariably of 24″ frame size. If a member of a cyclist volunteer battalion wanted a bicycle that was more suitable to his requirements, he would either take his own machine – as many did – or order one specially from one of the cycle manufacturers who supplied military machines. There’s an interesting story of an officer who was about to sail for South Africa who saw a colleague’s bicycle and wanted one similar. He contacted the company. They told him they could build him a bike to his requirements within one month. He explained that he was due to sail in four days! They replied that it was impossible to build a bicycle for him at such short notice …nevertheless, they did build it, with staff working day and night, and delivered it to the ship in time for his departure.

Compare this unencumbered 1898 Alldays Matchless with the fully loaded double top tube heavy roadsters of the City Imperial Volunteers (C.I.V.) in the photo below. With Carter chaincases and freewheels, the latter machines would have been manufactured at the turn of the century. It’s interesting to consider to what extent the Boer War influenced cycle evolution at this time: freewheels, gears and brakes – and luggage carriers – were developed and introduced to the market for the first time during the 1898-1902 conflict, these innovations providing a quantum leap in cycle design that remained virtually unchanged for the following half century.

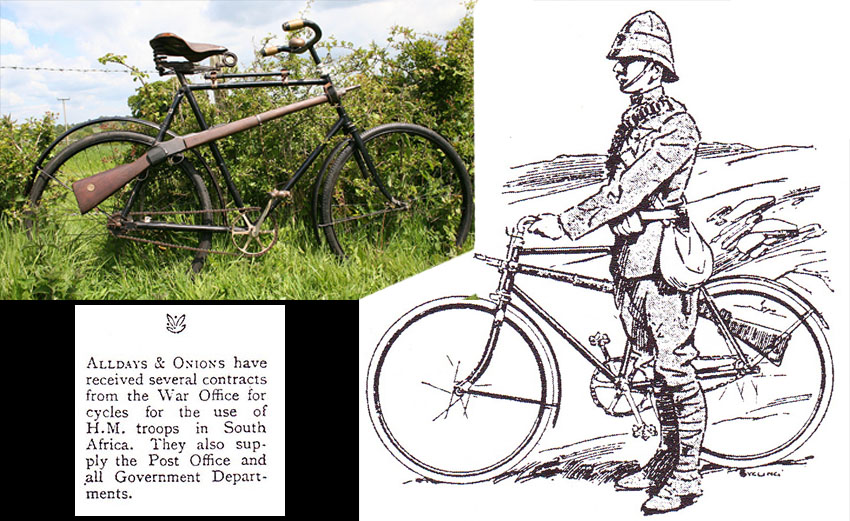

The C.I.V. had 1000 men, seeing action through the Orange Free State and Transvaal. Most of their cyclists were assigned to orderly duty between the docks and camp, their prime function throughout the war. When the force was on the move, bicyclists served as dispatch riders up and down the column, and between adjacent communities and military installations. As the company was already an established cyclist volunteer battalion, they used their experience to prepare their bicycles before leaving for South Africa. Cyclist J. Barclay Lloyd reported that they used rucksacks that had been recommended by an alpine mountaineer. In addition:

Each rider carried on his person a 100-round bandolier, full haversack and water bottle, a belt with pouch and bayonet, a carbon filter attached to a lanyard, a pair of field glasses, a knife and a compass. On the bicycle was a mackintosh rolled up and tied to the handlebars, a rifle in a bucket attachment, and on the back a carrier that held a rolled greatcoat, blanket, waterproof sheet, and the rucksack, inside which were clothes and a mess tin. The alpine rucksacks could be worn by the rider or strapped on the cycle, as circumstances required. By loosing a single strap, they could drop the heavy kit from the back of the machine, ‘ready to go on light quick work.’

…On sandy soil, Lloyd found that mounting and getting the laden machine underway was sometimes difficult. Nevertheless, over a wide variety of terrain and across diverse riding surfaces, he could still far outpace infantry troops. The cyclists were better off in that they could carry on their machines ‘without hindrance or discomfort, far more than a man can bear upon his back.’ On one 90-mile infantry march to Bloemfontein, which took seven days, the accompanying cyclists peddled leisurely along. As infantrymen began falling out from illness and injury, C.I.V. cyclists were ordered to pedal up and down the two-mile long column and assist their marching comrades to reach the adjacent railway line, where passing trains picked them up and conveyed them on to Bloemfontein.

On the field of battle, when a Boer position was charged, there was usually ‘a cyclist or two with the leading rank, while others will be scattered over the field conveying messages.’ On one occasion, when his regiment was engaged in a running fight with the Boers, Lloyd had alternatively to carry and drag his heavily laden machine up and over boulders to the top of a steep kopje; it was then that he concluded that ‘a bicycle is not an unlined blessing.’

When their camp lay within 30 miles of a large town, the cyclists had their busiest times. They would convey mail, telegrams, dispatches, and reports of numbers of troops killed or wounded to the major centre, then pedal back with stores, groceries, and money for payment to troops. Although such round-trip journeys could easily be done in a day, the cyclists sometimes rode at night to minimise encounters with enemy patrols.

One matter Lloyd complained about was the tendency of officers to miscalculate distances, even when they had detailed maps available. Distances measured by him and his colleagues with their cyclometers routinely disagreed with the official estimates, often by half. On occasion it caused great stress for the infantrymen and once resulted in the unnecessary death of several animals when the officers tried to force the column to cover took much ground over a given period.

Lloyd found that much of the veldt was rideable, but was covered by a thinly growing thorny scrub that tended to puncture all but the stoutest tyres (the long, sharp mimosa thorns came in for special attention). He never noted whether whether any of the riders tried the Australian Dunlop Thorn Proof tyres which were highly resistant to puncture. Those tyres had in fact been developed in Australia partly in response to the incidental importation into that country of a native South African thorny plant. He found travel along railway lines relatively pleasant by pedalling on the adjacent paths used by maintenance crews. However, on occasion, he rode between the rails when the ballast stones were not too large and covered the sleepers sufficiently for a smooth ride.

The roads and tracks sometimes were very bumpy, and with many sandy patches which could be particularly difficult to pedal through. Overall, however, Lloyd concluded that ‘the bicycle is a most useful method of progression’ with the large number of ‘fine roads,’ good veldt tracks and native footpaths making the widespread use of the machine feasible and successful. A witness at the Royal Commission on the War in South Africa testified that he was ‘astonished’ by the way the City Imperial Volunteers cyclists got about on the veldt.*

1898 Alldays Matchless Military Roadster

24″ Frame

28″ Wheels

Coaster Brake

ALLDAYS & ONIONS LTD

This 1898 machine predates the Military Pattern cycle, introduced by the War Office in 1901. Alldays & Onions reported a contract for the supply of 800 military bicycles in February 1901, which would most likely relate to Mark 2 pattern machines, as shown in the 1908 Alldays catalogue illustration below.

Compare the 1908 Alldays catalogue illustration above with the Mark 2 pattern shown below.

Alldays was also a major supplier of tradesman’s bicycles, including contracts with the Post Office. Military bicycles and tradesman’s bicycles are each heavy duty machines, with many parts in common.

ALLDAYS & ONIONS LTD

Alldays & Onions was England’s oldest engineering company. Though the company claimed its formation was dates ranging from 1650 and 1780, the union of the two Birmingham companies actually took place in 1885 when William Alldays & Sons, of Branston St, and J.C Onions, of Bradford St, merged to form the company of Alldays & Onions Ltd. However, a craftsman named Onions is believed to have been making bellows in a shed near Dudley Castle in 1625 ands some twenty five years later the brothers Onions had established a business in Birmingham where, in 1770, a John Onions was known to have a bellows making business in Digbeth.

Edmund Allday had taken out patents concerned with the design of velocipedes as early as 1889, and in 1896 the company established a new cycle factory, at Matchless Works. As the company was already well-known for quality products, orders for cycles followed as soon as the company was ready. Adverts had been placed even before their cycle factory had been built. In December 1896, the company reported that cycles made from their patented corrugated steel tubing had proved so popular that they had been unable to supply the demand. At the Stanley Show that year one cycle from the huge order received from the British South Africa Company was shown resplendent in its red enamelled finish and complete with attachments to carry a rifle and a sword.

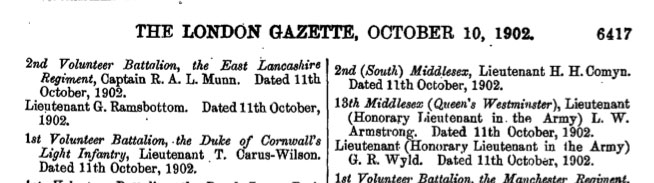

The War Office gave Alldays their first large government contract in 1898 which was rapidly followed by four more contracts and in February 1901 by the largest contract to be awarded to the company so far, for 800 cycles. One of the exhibits at the 1902 Stanley Show was a military cycle used by a Lieutenant Carus-Wilson during the Boer War. Records indicate he served with the 1st Battalion, the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry and the ‘Composite Cyclist Corps’ and and sailed for South Africa in July 1902. He also served in WW1, but did not return from that war:

Lieut. Colonel Trevor Carus-Wilson, D.S.O. (1916), Mentioned in Despatches thrice, commanded 1/5th. Bn. from 11 January 1917, died of wounds France, 27 March 1918.

Carus Wilson was an old Volunteer and Territorial, and served with the Composite Cyclist Corps in South Africa during the Boer War, where he had considerable experience of Lord Kitchener’s block house system, and was awarded the Queen’s medal with five clasps.He was educated atShrewsbury School, after which he spent some time in the G.W.R. Works at Swindon. Following a visit to Mexico he settled down in England, joining the Engineering Department staff in 1899, and at the time of mobilization in August 1914 was an assistant to the New Works engineer.After mobilization he was at first engaged in guarding the wireless station at Poldhu, and later was sent to India and served on the Viceroy’s Guard of Honour.On returning in December 1915 he was appointed as Major in the 5th Batt.Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry, then being formed, with which he proceeded to France in the following May, being from the end of 1916 in command of the unit. He was three times mentioned in despatches, was awarded the Territorial Decoration last December, and received the D.S.O. on March 17th.He was a man of attractive disposition, and his loss is deeply regretted.

* The Bicycle in Wartime, pp 64-67, by Jim Fitzpatrick, quoting J. Barclay Lloyd, One Thousand Miles with the C.I.V.

Carus Wilson: with thanks to – http://www.zoominfo.com/s/#!search/profile/person?personId=184327088&targetid=profile

Alldays history – with thanks to Alldays & Onions Pneumatic Engineering Co Ltd by Norman Painting, 2002