In the autumn, the nation was struggling to come to terms with the catastrophe of the First World War. Nearly three quarters of a million British men were estimated to have died and more than a million and a half had been severely wounded during the conflict. Almost no surviving individual escaped the grief of losing a husband, father, son, fiancé, uncle, cousin or friend. But the 1918-1919 influenza virus was just about to make matters even worse.

Those afflicted were first aware of a shivery twinge at breakfast. By lunchtime, their skin had turned a vivid purple, the colour of amethyst or the sinisterly beautiful shade of the heliotrope flower. By the evening, before there was time to lay the table for supper, death would have occurred, often caused by choking on the thick scarlet jelly that suddenly clogged the lungs. Between 50 and 100 million people across the world died of what became known as Spanish Flu.

A browse through that autumn’s newspapers confirms the post-war conclusion of the poet T S Eliot that ‘humankind cannot bear very much reality.’ Stories of the new epidemic were buried deep within papers, often at the bottom of the page. The General Medical Council discouraged the use of the word ‘pandemic’ but the escalating death rate was impossible to ignore, swelling the increasing fear of the disease. Some countries introduced legislation to try and combat it. In Arizona they outlawed handshaking; in France, spitting became a legal offence.

Doctors dispensed alternating suggestions either for rejecting all alcoholic beverages or for taking regular tots of whisky, the age-old remedy for all ills, including fear itself. Some recommended half a bottle of light wine a day, as well as a glass of port before retiring to bed after a very hot bath. Tobacco was generally thought to exacerbate the illness and was mildly discouraged. Oxo spent millions on advertising its meaty drink supplement as a good way of increasing nutrition and ‘fortifying the system.’

Huge numbers of the influenza-suffering public relied on their own resources. Older people fell back on trusted household remedies for illness: laudanum, opium, quinine, rhubarb, treacle and vinegar were all invested with special healing powers.

But none of these antidotes provided an infallible cure and the authorities struggled as the epidemic took hold. In London, nearly 1,500 policemen, a third of the force, reported sick simultaneously. Council office workers took off their suits and ties to dig graves. Coffins that had been stockpiled during the war (a wartime agreement had been made that no bodies would be brought back from the battle lines) were suddenly in short supply. Railway workshops turned to coffin manufacturing and Red Cross ambulances became hearses.

Whole classes of children were kept away from school by their wary parents, filling instead the city’s playgrounds and singing:

‘I had a little bird. Its name was Enza.’

‘I opened the Window. And in-flew Enza.’

To cheer themselves up, people went to the cinema. Lillian Gish with her fragile beauty was the most popular film star of the year. Her name had been adopted at Billingsgate fish market as part of the traders’ rhyming slang, crying: ‘Fancy a nice bit of Lillian for your supper tonight?’

Arriving from a bus liberally sprayed with disinfectant, people settled down to watch the latest Gish weepie, Broken Blossoms, sometimes spending the whole day in the cinema, as reel followed reel. Councils insisted cinemas be emptied every four hours to allow windows to be opened to aerate halls, but the manager of the Coronet in Notting Hill refused to disturb his customers. He claimed his special aerating machine still worked while the audience remained in their seats. The bug-ridden air was never given a chance to escape and the infection was redistributed around the auditorium.

– from ‘The Great Silence 1918-1920: Living in the Shadow of the Great War’ by Juliet Nicolson (published by John Murray)

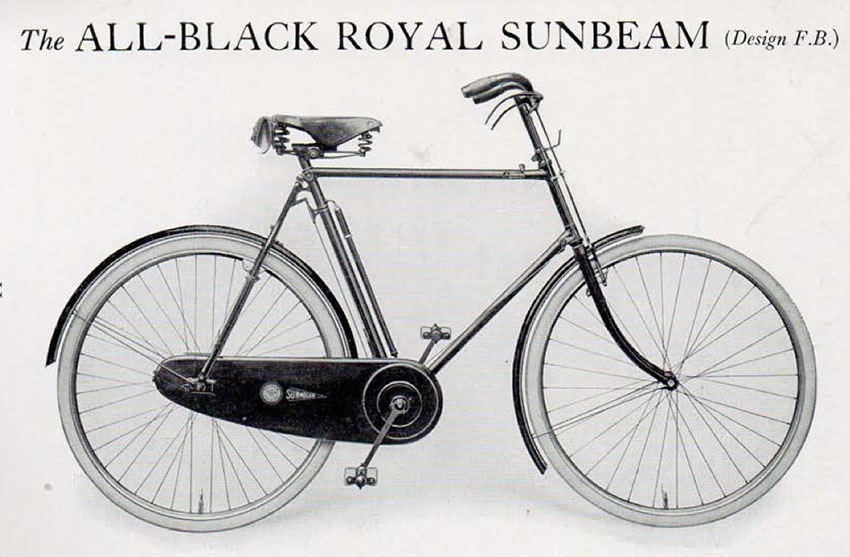

It was not until I read Juliet Nicholson’s book (above) that I fully understood the Sunbeam advert (below) from their early 1920s catalogue. The company advocated the use of a bicycle to commute to work as the best way to avoid catching the flu in public places such as the tram or railway carriage.

This 1923 Sunbeam has a large 26″ frame, suitable for a chap around 6′ height or more, and inside leg around 35″.

The optional three-speed gear in the rear hub is much easier to maintain than the two speed epicyclic gear. It cost an extra guinea when new.

The bike is in good mechanical order and ready to ride. The transfers (decals) are missing, though are available if you wish to fit them. The leather saddle is period style and in good condition; it is made by ‘Kosmos.’ The chain case cover is missing. The mudguards are from an early 1930s Sunbeam. The handlebar grips are replacements. Otherwise the bike is original.