22nd May 1946: A new BSA model is now making an appearance in dealers’ shops. It is named the Paratroop, the twin-tubed oval frame being based on the now-famous BSA exclusive design of folding bicycle for airborne troops that did such a fine job in the liberation of Europe. It has a 20-inch frame, with forward drop-out ends, forks with brazed-in ends, 26 inch wheels, oval cranks, rubber pedals, chainguard, North Road upturned bars, caliper brakes and Brooks spring-seat saddle.

The finish is an attractive green with gold lining and chromium plated bright parts, and a hold-all bag is supplied. This model, 904ACP, is a very smart and attractive looking machine and although it is the first new BSA to be announced since the end of the war (apart from the BSA Junior Parabike), it is emphasized that it does not incorporate the new BSA features which will not be made known until the specifications of the post-war range are published.

– Cycling Magazine, 22nd May, 1946

The BSA Paratroop ACP was more-or-less unknown in Great Britain in the 21st century, until it was researched by my friend Dave Williams in Bristol when he found one in 2002 and wrote to BSA to ask what it was. Although it was not well-documented, he discovered that as well the postwar Junior Parabike that followed the styling of the wartime BSA Airborne folding bike, the company made this full-size paratrooper-style model too. The implication in the recollection of Mr.Cave, manager of BSA at the time, was that the ACP was a continuation of the BSA Airborne in civilian form, ie using some of its parts and tooling.

Here’s the reply he received from BSA:

I’m sorry it has taken me a little while to get back to you. I carried out a few more searches myself but these proved fruitless. However, the good news is that Mr. Cave has been into the library and I have managed to discuss your enquiry with him in person. (I think I mentioned Mr. Cave to you in my last letter – he was Manufacturing Manager at BSA from 1941 to its close in 1975). He was able to supply me with the following information.

Your cycle is one of the BSA Airborne cycles which were manufactured for the British Airborne Forces between 1938/39 and 1944. 64,000 were manufactured in total. After the war, an attempt was made to carry on manufacturing this cycle in civilian form and make it available for the public to buy. Your cycle is one of these. They were made 1945/6, and only a few were made, making the few left in existence very rare!

I bought Dave’s ACP some years ago, but he subsequently complained that he regretted selling it. So when I found this one in America, I returned his old ACP to him.

1946 BSA Paratroop Model 904ACP

(Army Commando Paratroop)

BSA Three-speed

26″ wheels

EXTREMELY RARE CIVILIAN VERSION

of the popular WW2 Army BSA Airborne Folding Paratrooper Bicycle

BSA’s First postwar Bicycle

AMERICAN EXPORT MODEL

This is an American Export version of the BSA Paratroop, retaining the shop transfer (decal) on the rear mudguard for Rich Child Cycle Co, who had the main East Coast BSA agency at the time.

By the Second World War, BSA had 67 factories and was well-positioned to meet the demand for guns and ammunition. BSA operations were also dispersed to other companies under license. During the war it produced over a million Lee-Enfield rifles, Sten sub machine guns and half a million Browning machine guns. Wartime demands included motorcycle production: 126,000 BSA M20 motorcycles were supplied to the armed forces. At the same time, the Daimler concern was producing armoured cars. And, of course, BSA also manufactured Mk.V and Airborne bicycles.

During the War, British industry was effectively nationalized. Though, in 1945, British vehicle manufacturers started to return to peacetime production, de-nationalization was a gradual process. Nearly all motorized vehicles were exported to bring in much needed foreign exchange: Great Britain had a massive war debt to repay to America, and much of it was repaid through exports.

Bicycle manufacturers played a major part in this export drive too. For example, in their first year of operation, 1946-1947, Mercury Industries (Birmingham) Ltd quoted £1 million in export sales.

BSA expanded greatly after the War, buying Triumph, Ariel, Sunbeam and New Hudson. As a result, they became the world’s largest motorcycle producer. They already had an excellent reputation around the world and, as well as motorcycle exports, the company shipped out their range of bicycles to far-flung corners of the world.

***************

THE BSA 904ACP PARATROOP

This model did not appear in BSA catalogues. It was a stop-gap model, produced only in 1945 and 1946: by the time the new BSA range had been introduced, it was dropped.

These adult cycles were not successful and production ceased. It was, however, very successful when it was manufactured as a child’s bike – both as 14 and 16 inch wheel versions. Several thousand of those were made seasonally each year based on a hinge version of the bike. These cycles weren’t sold under the BSA name but the Sunbeam name.’

My assumption is that the BSA ACP was initially considered for sales abroad, particularly in America.

My reasons for this assumption are as follows: America was the primary export market, being the world’s richest country at the time. British Exports were written off against war debts. Victory was still fresh in the public’s mind, and a bike that looked like the famous BSA Airborne would have been a good marketing idea. The war was used as a marketing strategy well into the fifties: for example, ‘war grade’ tyres were sold for many years after the war, and the American manufacturer Columbia marketed a ‘Paratrooper’ model which was not even used during the war. While, postwar, the British bicycle market was an adult one, America’s postwar bicycle market was youth-orientated. In the USA, by age seventeen, kids had cars. This is undoubtedly a young person’s style of bike.

Also, compare the design of this frame with that of American bicycles of the era. By 1941, influenced by 1930s American cars and trains, the styling excesses of American bicycles had reached its zenith. I’d not thought about it before, when looking at the folding version. But, seeing this non-folding model, I wonder if the design of the BSA Airborne itself had its origins in the aerodynamic styles of prewar American bicycles?

But why was it dropped from production?

– The answer (my own assumption) is very simple. The 1946 price of the new BSA Paratroop Model 904ACP was quoted as £10 14/- 6d plus purchase tax £2 10/- 1d. That makes a total of £13 4/- 6d. Now look at the 1954 advert below: it offers a military surplus BSA Airborne bike for 70/- (£3 10/-).

The comparative saving of nearly £10 is not accurate bearing in mind that this advert is eight years later, but it does illustrate the fact that a lot of second-hand folding machines came onto the market after the war, and they would have competed directly with the Model 904ACP. Though they were second-hand, they had another advantage besides price – they folded!

*************

A most interesting footnote can be found in Pashley’s latest model. It’s called a ‘Tube Rider.’ You can see it below. Is there something vaguely familiar about it? 🙂

BSA ACP v BSA JUNIOR PARABIKES v BSA AIRBORNE FOLDING PARATROOPER BIKE

The BSA Junior Boy’s Parabike is a scaled-down version of the BSA ACP. While the ACP was discontinued within a year, the children’s Junior Parabike models were sold until the early 1950s. I’ve not seen mention of the Junior models before 1946, so maybe it was made to replace the ACP.

They share the duplex frame construction, seen more clearly in the picture of the Boy’s Parabike below.

MY FIRST VIEW OF THE ACP

These were the first photos of I saw of this ACP in the USA. Joe, a bicycle dealer friend in America, had just put it onto US ebay, so I grabbed it quickly because of its original paintwork and parts. I already had an ACP, one of only three known to have survived; I had bought that one from my friend Dave in Bristol. Dave often bemoaned the fact that he’d sold it to me. So, after buying this one I let Dave have his ACP back.

Rich Child Cycle Co,

Nutley, NJ USA

As Harley-Davidson’s first export representative to Africa in 1922, Alfred Rich Child was used to breaking new ground. His career at Harley-Davidson also included serving as Managing Director of Sales in pre-World War II Japan, as well as negotiating the contract that would give Sankyo Company exclusive rights to manufacture Harley-Davidson products in that country. Following the war, Child founded the Rich Child Cycle Co., a distributor of BSA and Sunbeam motorcycles.

Born in Chichester, Sussex, England in 1891, Child was the son of a retired British Navy officer. He graduated from the Greenwich Royal Naval Academy in 1907.

Making his way to the United States by working as a steward for the Cunard line, Child worked various odd jobs, eventually starting his own traveling clothing supply business serving the grand estates on Long Island. His choice of delivery vehicle was a 1914 Harley-Davidson sidecar outfit.

After the start of World War I, Child joined the U.S. Coast Guard and served as a petty officer. While serving at the passport office in New York City, he met David Weistrich, who owned a wholesale bicycle parts business (including New Departure hubs, for which he had a wholesale franchise). In 1918, Child joined Weistrich’s business as a traveling representative to the southern states. Once again, Child’s transportation choice was a J Model Harley-Davidson with sidecar.

When Weistrich became ill and relinquished control of the business to his brother-in-law, Child began looking for new sales opportunities and applied with the Harley-Davidson Motor Company. He soon received a telegram from sales manager Arthur Davidson, and the two met in New York. After some discussion, Childs was hired and assigned to domestic sales for the northeast United States and eastern Canada, followed by sales positions in the southern states and eventually in Harley-Davidson’s hometown of Milwaukee in 1921.

An interesting insight into prejudices of the time is Arthur Davidson’s concerns that Child might be Jewish, because his previous job had been for David Weistrich. Says Harry V. Sucher ‘Upon being assured of pure Aryan background, Davidson next enquired whether his business and ethical concepts had been unfavourably influenced by his connection with a Jewish-owned firm. While this episode might appear preposterous in the light of today’s racial and ethnic tolerance, such was not the case in the USA in the early 1920s. As white anglo-saxon culture was predominant in America, most people were suspicious of foreigners and ethnic prejudice did not materially abate until well after WW2.’ [The Antique Motorcycle; article Winter 2005]

Upon returning from a tour of Europe and South Africa on Harley’s behalf, Child was informed that he should prepare himself for a survey of the Far East markets. Child arrived in Yokohama, Japan in July of 1924.

The Asian markets represented a challenge to Harley-Davidson. Not only was the Indian brand firmly entrenched there and importing 600-700 units a year, but the existing Harley-Davidson distributors were not ordering spare parts and were competing with each other in conflict of their contracted distribution territories. After lengthy attempts to resolve the problems, Child chose to sever ties with the existing distributors, but did maintain relations with one successful dealer.

The Koto Trading Company was a division of Sankyo, a large pharmaceutical manufacturer based in Tokyo. Unbeknownst to their management, Koto had been the recipient of “bootleg” shipments of Harley-Davidsons that were supposed to be sold in Mongolia – but were instead diverted to Koto in Japan – in conflict with Harley-Davison’s distribution agreements. However, Koto had been very successful and had sold all the inventory originally intended for Mongolia.

In August 1924, Child returned to Japan with an agreement with Harley Davidson and the Koto Trading Company to establish the Harley-Davidson Motorcycle Sales Company of Japan, with Child acting as managing director. The company set up shop at Kyobashi Crossing in Tokyo with a supply of 350 motorcycles and $25,000 in spare parts. Within the next two years, Harley-Davidson sales in Japan eclipsed those of Indian and the Harley-Davidson Motorcycle Sales Company of Japan was doing a brisk business in replacement parts.

While other brands of motorcycles were being imported for the Japanese market, only the Harley-Davidson was built as a commercial carrier and could be used to carry everything from candy to cement. Childs and his staff exploited this fact to great success. The well-connected Sankyo firm also convinced military and other government institutions to adopt the Harley-Davidson.

A fluctuating yen led Child to the idea of manufacturing Harley-Davidsons in Japan. With backing from the Sankyo company, in 1929 the Harley-Davidson Motorcycle Sales Company of Japan established the Shinagawa factory, the first motorcycle production factory in Japan.

In spite of the success of the Harley-Davidson Motorcycle Sales Company of Japan, changing business relationships forced Child to leave the company in 1936. He immediately started Nichiman Harley-Davidson Sales in Tokyo, importing Harley-Davidsons from Milwaukee, and ran that operation until 1937, when a nearly eight-fold import tariff increase combined with national political tensions made it impossible to continue business.

Child returned to the United States and in 1945 obtained the national distributorship rights for BSA and Sunbeam motorcycles by the Rich Child Cycle Co., Inc., which was sold to BSA Motorcycles Ltd. England in 1954.

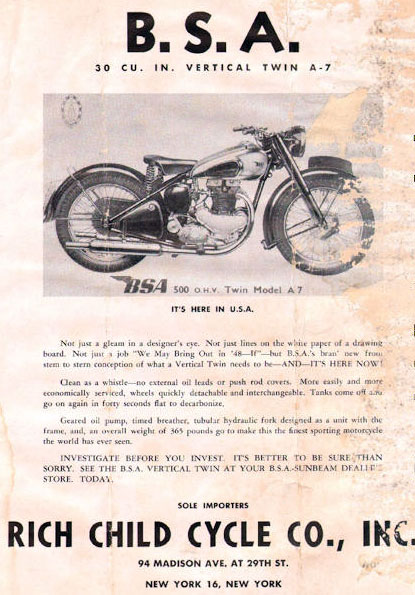

Popular Science Sept 1947

Popular Science Sept 1947

ROLAND PIKE’S EXPERIENCES OF ALF CHILD

The BSA representatives in the USA, Alf Child in the east and Hap Alzina on the west coast both realised the importance of racing for sales success in this market, and both were in favour of factory co-operation in these endeavours. In 1952 Alf Childs was in England for the Motor Cycle Show and while at the factory told the Board of Directors that he wanted someone to come over for several weeks and run a service school. Someone who can talk to the Dealers in their own language and who had some personality. I understand there was some talk of sending Fred Rist, he had been over before and had gone down very well, but he was not a technical man. Mr Hopwood suggested that perhaps they would like to meet Pike, he had been a motor cycle racer, has had experience and would be interesting to the Dealers and racers.

The first I heard of this suggestion was when I received a telephone summons to Mr Leake’s office, my first thought was to wonder what I had done wrong. After a quick tidy up I went up to the office and was escorted by Mr Leake’s secretary to the boardroom where the Directors, Mr Hopwood and Alf Child were waiting. They introduced me to Mr Child who sized me up and said I looked a dignified young man and how would I like to go to the States and run a service school? I looked across to Mr Hopwood and asked if he thought I knew enough about the rest of the bikes, and he said he would arrange it for me to obtain the necessary knowledge if I thought I could run a school. It was all laid on very quickly, the Motor Cycle show was in October and I was wanted in the States by November.

Due to the rather rough crossing the boat was slowed and the trip took eight days instead of the usual six or seven scheduled. Passage was booked on the 14,000 ton cargo boat HMS Media. We finally arrived in New York harbour on a Sunday morning. I had never seen so many cars and traffic on the beltway. After driving through the Lincoln Tunnel we passed through towns with to me strange names like Hackensack and Passaic finally reaching Nutley, NJ where I booked into a motel for one night with the arrangement that Roy would pick me up in the morning and have breakfast together. The motel was steam heated, and I having always been used to cold bedrooms opened up the windows as I felt I could not stand the stuffy atmosphere, however by morning it was cold enough for me to regret being so rash. After breakfast Roy took me to Rich Child Cycle Co and I was introduced to a bewildering crowd of characters, most of whose names I forgot almost immediately.

The schedule arranged for me was to, start a school that same morning which did not leave me much time to prepare, none of the bikes or literature had arrived but I did have the two films. It was my first introduction to American motorcyclists who appeared to me to be in some type of uniform, leather jackets and peaked hats not unlike Nazi Storm troopers and some had Harley Davidson emblems on. They appeared to be a tough looking crowd but in actual fact were a friendly bunch. We soon settled in-to the Service Department which Bill Carlton the Rich Child mechanic had turned into a class room for the week with blackboard, easel and chairs. Showing one of the films gave the fellows a chance to relax as most had been travelling over the weekend to attend the school. One had ridden his Star twin all the way from El Paso in Texas 2,500 miles, and he was not a youngster either, it had taken him nearly a week. In talking to these Dealers during the lunch break and in the evenings when we went out to eat I discovered that most of them were working as dealers part time, one of them ran a radio and electrical shop, motor cycles were a side line. Another worked in a factory all day whilst his wife ran the bike shop and he sold and serviced bikes in the evening. If he sold a couple of bikes a month he was happy. There was one who ran a full time shop in New Jersey and another in Washington, Long Island , but these were the exception. Most worked only part time in the cycle business which may be why BSA did not sell as many bikes as Honda did later on, as Honda built up a proper dealership network.

Shortly we had our materials unpacked and talked about the new models and what was coming along for 1953. They were interested in what I did at BSA and how the factory was organised, we showed the films of Scramblers and of the Ulster Grand Prix in the wet in 1948. They could not understand how the bike could do 100-120mph in the pouring rain and not slide off the road. They were also interested in my own racing experiences.

The actual Service part of the course was a bit haphazard, some would bring up a problem, we would discuss what we knew of it and a possible cure, to me it did not seem they we were accomplishing very much, but they went away at the end of the week apparently quite satisfied. On the Friday we went into some details of the Ariels, which I knew only a little about but Bill Carlton and one of the roadmen were able to cope quite adequately. Alf Child, Roy Bradbury and myself sat down on the Saturday and held a review of the first week, Alf wanted more emphasis on sales, so Roy had to lay on a bit of high pressure stuff and he suggested I talk more about the Star twin, so I prepared for that. The second week with a fresh group of Dealers went off better. Roy warned me that the third week was likely to be the toughest as the Dealers expected were practical men and likely to be argumentative. He kindly pointed out the most likely trouble shooters, one in particular was Herb Suddeth but as it turned out he was the most helpful co-operative pupil of the whole three weeks and I got along with him extremely well.

On my return to the factory I had to give a report of my trip for the management and it was read out at a meeting and met with their approval, so much so that I was asked if I would be willing to go again in 1953 to Daytona. I knew many of the US dealers had asked if I could come for Daytona as they thought I would learn a great deal more of their requirements for short track events. Evidently Alf Child had approached Mr Leake with their request. The results were that in February 1953 I was aboard the Queen Elizabeth heading for the States. This time I sailed from Southampton and it was much more ‘de luxe’, even Cabin Class on the Elizabeth was more comfortable than first class on the Media.

The voyage across was luxurious but uneventful, I spent three days at Nutley preparing for the trip to Daytona. Alf Child and Mrs were flying and wanted to take me but I preferred going by road with Bill Carlton as I felt it would give me more time to see the country. We were taking a half ton van loaded with all manner of spares, even complete engines, catalogues and literature for the bike show in Daytona.

Came the start of the big race and Bobby Hill stalled his engine, it looked as if the chance for a win by the number one champion was nil, all the competing BSA twins, BSA Gold Stars, Triumphs and Harleys were long gone, however the referee motioned to Hills mechanic to give him a push start and away he went. It was a twenty lap race event and unbelievably Hill worked his way up through the field to win. I had never seen anything like it, that was my first introduction to Bobby Hill. Later he used BSA doing extremely well on them, winning Daytona in 1954 on a clubman type twin.

After the racing we returned to Bob Kings staying another night in the motel. Next morning after some difficulty to change some GB travellers cheques only by going to a bank we drove on down to Daytona Beach, we found ourselves an apartment about two miles down the beach, we did this on advice from Cyril Halliburn and Bob King to avoid having riders bother us twenty fours hours a day. It was a very nice place with a view of the ocean but rather far out and you needed transportation to get to the BSA headquarters which that year were in the old Hudson dealers service department. We had the use of half the garage for BSA servicing and all the dealers and their riders came crowding in, talking and getting in the way. Alter unpacking our parts and tools we proceeded to service our machines. This being 1953 all we had were the heavy plunger rear suspension, iron barrel, alloy cylinder head Star twins. They were supposed to put out 43bhp, but we were experiencing valve spring problems. The prototype built in the Engine Development did put out 43bhp but all the Star Twins sent to Daytona were built by Production and tested in the engine test by Cyril Halliburn, who issued power curves showing 43bhp but when we got them to the beach for practice it was obvious that they did not have the power and were getting passed by all and sundry.

There were three of the previous years Star twins there, one of which had been hand built by Jack Amott, it was considerably faster than the new 1953 models. I would have liked to get a look inside that engine. In the race these wretched twins we had brought folded up one after the other, Warren Sherwood nursed his home into fifth place, the rest were nowhere. Paul Goldsmith won on a Harley and was sporting enough to come over to us and commiserate. One of our riders fell of and broke a leg. I persuaded Alf Child who owned the machine anyway, since the Dealer now declined to pay for it, to let me take it back to the factory and test it on my dyno, to which he agreed, remarking they were not as good as the previous years machines. As you can imagine he was pretty miffed with me, the bikes and the race results. I did not feel it was my fault as I had only been at BSA ten months and had not built any of These machines. The company was not too pleased to see the crashed bike but Bert Hopwood agreed that it was a good idea to test it and rind out why it was running as it did arid to then try and get the bugs out of it. Back on the dyno we got 39bhp and it took a good deal of work to get it up to 43.

The Directors asked me to come and give them a talk on my experiences in the US at Daytona particularly, as Alf Child had complained to them about me. Naturally I was not going to let him get away with this and I told my side of the story, particularly my dislike of being sworn at in a hotel in front of a whole crowd of people. Mr Leake wanted to know the exact wording which I was not keen to repeat, but he insisted, he queried my repeating and wanted to know why such an occasion had occurred. It was due to my late arrival at the garage to work on the bikes and I explained to Mr Leake we were situated nearly three miles from the garage and it was difficult to get a lift and on this particular morrning they had forgotten to collect me as arranged. Mr Leake appeared rather annoyed with Alf Child and complained to him of his attitude, this in turn upset Alf Child and I did not get invited to Daytona again.

YOU CAN READ MORE OF THIS ARTICLE HERE – http://www.beezanet.com/daytona/RP_chp_28.htm

TIME MAGAZINE

Bicycles from Britain: Monday, July 5th, 1954

The following article in Time Magazine from 1954 provides interesting insights into the British bicycle industry’s postwar US exports. Of course, it neglects to mention that the reason behind the aggressive British export drive to the USA was the need to repay the massive USA loans to Britain made during WW2 to help us fight Germany:

Outside a busy factory in Birmingham, England last week, ‘Help Wanted’ signs went up for 200 workers. The Hercules Cycle & Motor Co., one of the Big Three of Britain’s thriving bicycle industry, was adding a new assembly line to feed the hungry export demand for British bikes.

The hungriest customer is the U.S. Before the war, Britain shipped only 4,000 bikes a year to the U.S. This year imports rose to 110,000 during the first four months (usually the slow season). This was too much success for U.S. bikemakers, who demanded a boost in the tariff (now 7½% to 15%).

Spurred on by such complaints, the U.S Tariff Commission announced last week that it would investigate charges that imports are hurting the American industry. (Two years ago a tariff boost was denied.) The British, say U.S competitors, can produce bicycles and land them in the U.S for less than the cost of U.S manufacture. This is partly because of lower wage rates (about 58¢ an hour, v. about $1.80 in the U.S). But it is also because the British, who invented the foot-pedaled bicycle, have adopted the U.S invention of mass production. Britons can make bikes cheaper because their production, twice that of the U.S., is concentrated in three companies, while most U.S manufacture is scattered among ten.

The fad for British bikes got a big boost from the 5,000,000 U.S servicemen who served in Britain during the war and became acquainted with the trim, lightweight British bicycle (28-33 lbs, v. the typical 55 lbs in the U.S). The bikes also caught the fancy of U.S youngsters, who liked such grown-up refinements as generator-operated lights, hand brakes and three-speed gear systems. On top of that, the British aggressively advertised and ballyhooed their product, e.g an 8,000-mile U.S tour by a London bus covered with advertising placards.

They also tied up with sellers who knew the American market, thus won allies to keep tariffs down, since some of the sales agents are also manufacturers. Last year Hercules, a subsidiary of Britain’s big Tube Investments Ltd, made a deal to have its bikes distributed in the U.S. by the Cleveland Welding Co, a subsidiary of American Machine & Foundry Co, along with the U.S. firm’s own balloon-tired Roadmasters.

Raleigh Industries, Ltd., which has an assembly plant in Boston, this spring started to supply all the lightweight bikes for Huffman Manufacturing Co. of Dayton, Ohio (Huffy). B.S.A. Cycles Ltd last month bought out the Rich Child Cycle Co of Nutley, N.J, for many years one of its distributors in the U.S, and plans to make lightweight bikes in the plant.

To keep tariffs down and to forestall quotas, the British will rely most heavily on the argument that they have not hurt U.S sales but have created a new U.S market. Despite imports of 600,000 last year, sales of U.S. bikes have also gone up. from 1,252,000 in 1939 to 2,005,806. Says Hercules Boss Arthur Chamberlain (Cousin of previous Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain):

‘We feel sure there is a parallel demand for both American and British machines in the American market . . . Older teenagers … are learning that cycling can be a form of sport and healthy recreation.’

The American market has also taught bike-maker Chamberlain a lesson about selling in Britain. For the U.S market, the company made a bike called the New Yorker, with more glitter, chrome and gadgets than was considered good taste in Britain. The model has caught on so fast in England that it is becoming the company’s best seller.

SOURCES:

Rich Child info with thanks to – http://www.adfarrow.com/new/heroesofharley/halloffame/hofbiopage8204.html?id=382