In 1898, the Spanish-American War increased newspaper sales, so several publishers raised the cost of a newsboy bundle of 100 newspapers from 50¢ to 60¢, a price increase that at the time was offset by the increased sales. After the war, many papers reduced the cost back to previous levels, with the notable exceptions of the The Evening World and the New York Evening Journal.

On July 21, 1899, a large number of New York City newsboys refused to distribute the papers of Joseph Pulitzer, publisher of ‘The World’ and William Randoplh Hearst, publisher of ‘The Journal.’ The strikers demonstrated across Brooklyn Bridge for several days, bringing traffic to a standstill, along with the news distribution for most New England cities. They kept others from selling the papers by tearing up the distribution in the streets. The boys also requested from the public that they no longer buy either paper until the strike was settled. Pulitzer tried to hire older men to do the boys’ job, but the men understood their stance and wanted no part in defying the boys. Several rallies drew more than 5,000 newsboys, complete with charismatic speeches by strike leader Kid Blink.

So named because he was blind in one eye, Kid Blink (Louis Ballatt) was a popular subject among competing newspapers such as the New York Tribune, who often patronizingly quoted Blink with his heavy Brooklyn accent depicted as an eye dialect, attributing to him such sayings as “Me men is nobul.” Blink and his strikers were the subject of violence, as well. Hearst and Pulitzer hired men to break up rallies and protect the newspaper deliveries still underway. During one rally Blink told strikers, “Friens and feller workers. This is a time which tries de hearts of men. Dis is de time when we’se got to stick together like glue…. We know wot we wants and we’ll git it even if we is blind.”

Although The World and The Journal did not lower their 60¢-a-bundle price, they did agree to buy back all unsold papers and the union disbanded, ending the strike on August 2, 1899.

Child labour was not an invention of the Industrial Revolution. Poor children have always started work as soon as their parents could find employment for them. But in much of pre-industrial Britain, there simply was not very much work available for children. This changed with industrialisation. The new factories and mines were hungry for workers and required the execution of simple tasks that could easily be performed by children. The result was a surge in child labour and, in industrial areas in Great Britain, children started work on average at eight and a half years old. There was a considerable campaign in Great Britain against child labour, culminating in two important pieces of legislation – the Factory Act (1833) and the Mines Act (1842). By the end of Victoria’s reign, most children were in school up to the age of 12.

Much of the Victorian child labour force in Great Britain and America was hidden from view; though articles and some books were written about them, few photos exist of them today. But in some professions they were in the public eye and there is a photographic record. In America these jobs include Western Union messengers, shoe-shine boys and news vendors, who were commonly known as ‘newsies.’

‘Newsies’ were the main distributors of newspapers to the general public from the mid-19th to the early 20th century in the United States. They were usually homeless children working until very late at night and earning around 30 cents a day. The boys did not actually work for the newspapers, but instead acted as independent agents, buying the papers to sell for that day. That meant they lost money on the unsold papers. As one newspaper writer of the late 19th cent wrote about them:

‘You see them everywhere…. They rend the air and deafen you with their shrill cries. They surround you on the sidewalk and almost force you to buy their papers. They are ragged and dirty. Some have no coats, no shoes, and no hat.’

1920s Overland News Vendors’ Coaster Wagon

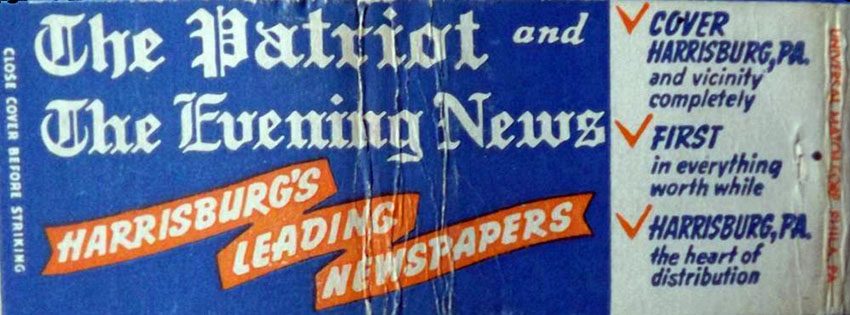

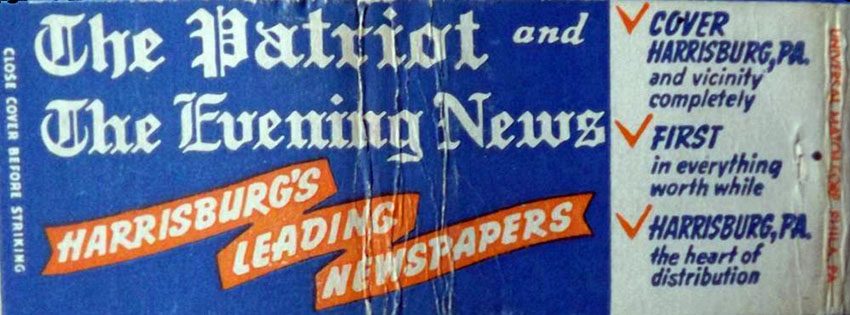

Harrisburg, PA: ‘The Patriot & The Evening News’

Manufactured by Hunt, Helm, Ferris, Harvard, Illinois

OVERALL LENGTH: 67″

BODY LENGTH: 34″

WIDTH: 14″

10″ Disc Wheels

This Overland is larger than most children’s coaster wagons – because, uniquely, it was not a toy. Whereas other coasters were used for rolling downhill or giving rides to baby sisters, this one was used by working children to carry the newspapers they sold. On each side of the wagon it is stencilled ‘The Patriot & The Evening News.’ On the rear is its name ‘Overland Coaster Wagon.’

The 1908 Overland coaster wagon in the illustration above is 30″ long with 6″ wheels – this advert is the earliest use I’ve seen of disc wheels. It has a much simpler front axle and handle than the example featured here. The news vendors’ Overland wagon is 34″ long with 10″ wheels.

I asked Gordon Westover – the ‘Wagonmaster’ – about the manufacturer of the Overland, and he confirmed it was Hunt, Helm, Ferris. The company is featured on page 52 of his new book ‘Coasting on Wheels.’

OVERLAND COASTER WAGON SPECIFICATIONS

BODY ” Clear white ash, natural finish, trimmed in red and stenciled in black and green.

GEARS ” Channel arch truss steel construction, enameled black.

FIFTH WHEEL” Extra large, made of steel.

AXLES ” One-half inch round steel, firmly braced front and rear.

WHEELS ” Heavy iron hub into which straight, smooth, kiln dried hardwood spokes are driven. Felloes and tires of heavy steel, electrically welded, with edges curled in to hold the ends of the spokes.

BEARINGS-Each wheel fitted with eleven cold rolled steel bearings, held in place by a special washer that does not wear cotter pin.

TONGUE ” Hard, straight maple which bends back and allows wagon to be steered from box.

Overland Coaster Wagon With Box Removed THE express box on all Overland Coaster Wagons can be in-stantly removed or replaced. The wagon may be changed from express to coaster in a minute.

A simple connection, easily operated, locks box firmly to the bed.

1908 CATALOGUE: OVERLAND COASTER WAGONS

HUNT, HELM, FERRIS & Co

Harvard, Illinois, USA

In 1883 Henry Ferris invented and patented the hay carrier. Charles Hunt, and his father in-law Nathan Helm, suggested Ferris move his shop into the basement of their hardware store in Harvard, Illinois. Soon they were selling the hay carrier in the store along with their other merchandise. And so, the Hunt, Helm & Ferris business began.

Through the years they manufactured more than 50 products and acquired more than 250 patents on equipment designed to streamline farm work.

The ‘Star Line Catalogue (No 78), published by Hunt, Helm, Ferris & Co in 1919, gives an idea of the range of products made: dairy barn equipment, stalls, stanchions, stock pens, litter, feed and milk can carriers. They were complete barn outfitters.

They also made coaster wagons and junior tricycles with the Cannon Ball name.

1926 HUNT, HELM, FERRIS ‘STAR LINE’ CATALOGUE EXTRACTS

OVERLAND AUTOMOBILE Co

In 1903, Cox designed and built a car with an advanced design at the time. In 1903, a new car with advanced design called the Overland featured a two-cylinder water-cooled engine mounted up front under the hood. The car also featured a removable switch plug so that it could not be driven without it. This first Overland was a ‘runabout,’ a small, inexpensive, open car. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the runabout was a common car body style.

In 1903, twelve Overlands were built and sales doubled in 1904. By this time, Cox was already designing the 1905 model of the Overland which would have a four-cylinder engine and a steering wheel. With the increased production, the Standard Wheels facilities in Terre Haute were too cramped. In 1905, Overland production was moved to Indianapolis where Standard Wheels had a plant that was not being used.

Work in the new plant had just begun when Minshill informed Cox that the automobile was not proving to be profitable and he didn’t think there was a future in it. Minshill wanted out of involvement with Overland production. This could have been the end of Overland, but David Parry, who had been a Standard Wheels customer, was willing to provide the capital for Overland in exchange for 51 percent of the company. Parry was a carriage maker who had tried to make an electric car in 1892 (it wasn’t drivable). Parry had seen the Overland and was impressed.

During the period after Minshall pulled out of the company and Parry joined it, Cox kept the factory open, employing just a few men and playing with possible new models. In 1906, the Overland Automobile Company was formed and headed by Parry. New production had just begun when the 1907 bank panic hit. Parry lost everything, including his house.

Automobiles were marketed to the general public through a system of dealerships. In Elmira, New York, John Willys had the Overland dealership. He had contracted for Overland’s entire 1906 production and had ordered 465 for 1908. He paid $10,000 in advance for the cars and was concerned when no cars were delivered. His customers wanted their cars. He tried to contact Overland by telephone and telegraph and got no response. To find out what was happening, he went to Indianapolis. When he arrived, he found that the company had gone bankrupt and no cars were being made. Willys immediately took over the factory, did an inventory, and found that there were enough parts to build three cars.

Willys paid off the workers what they were owed. He then erected a large circus tent and restarted the company. With tents grouped around the factory, Willys managed to build 465 automobiles. In 1912, the Overland Automobile Company was renamed the Willys-Overland Motor Company.

In 1917 there was a major strike at the Toledo plant and as a result the 1917 model Overland did not get into production until 1919. To take care of the problems at the Toledo plant, Willys hired Walter Chrysler to run the Willys-Overland operations. Chrysler, who had been vice-president at General Motors, was paid $1 million per year. In 1921, after unsuccessfully trying to take the company away from Willys, Chrysler left to go into business for himself.

In 1918, Willys, through his holding company, acquired the Moline Plow Company which manufactured both farm tractors and Stephens cars. The next year he acquired control of the Duesenberg company. Overland cars continued to be produced until 1926 when they were replaced with the Willys Whippet.

G. SOMMERS & Co

St Paul, Minnesota, USA

Early in November, 1882, retail tradesmen in the Northwest received a twelve-page circular listing various household products for sale at low prices. The circular bore the title ‘Our Leader’ and was sent by the firm of B. Sommers & Co (later G. Sommers & Co) of St. Paul, Minnesota. This event marked the beginning of a wholesale business which flourished for nearly sixty years (liquidated in 1941).

‘Our Leader’ was both a source list of merchandise and a challenge to the storekeeper. Its copy went to great lengths to induce, cajole, and persuade the retail merchant to purchase freely and promote his wares effectively. It emphasized constantly the firm’s basic policy of low price — a policy which led the company to call itself the ‘Western Bargain House.’ Low prices, good quality merchandise, strong mail-order advertising, and a growing reputation for honest dealing were the foundation stones of the concern’s success. By 1886, the company was selling to many types of retail outlets, including general stores, and grocery, drug, dry goods, hard-ware, and notions stores. Orders also were received from department stores.

Though of course the most famous Overland was the early American automobile, several companies used the Overland name for their wheeled goods. Gendron later made a ‘Toledo Overland’ pedal car in the 1920s and 30s. But some time between 1907 and 1915, the Davis Sewing Machine Co built a bicycle badged as the Overland for leading wholesale company G. Sommers & Co of St Paul, Minnesota. Sommers also marketed a toy train made by Hafner Mfg Co from 1907 onwards called the Overland Flyer. So it appears likely that ‘Overland’ was one of this company’s brand names.

1920s OVERLAND COASTER WAGON: UNDERSIDE

1921 CATALOGUE: OVERLAND COASTER WAGONS

HARRISBURG, PENNSYLVANIA: THE PATRIOT & THE EVENING NEWS

The Patriot is a newspaper from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania that was first printed in 1854. The company began circulating The Evening News in 1917.

1899 Newsboy strike info with thanks to – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Newsboys%27_strike_of_1899

Newsies info with thanks to – http://ants-and-grasshoppers.blogspot.co.uk/2014/09/kids-in-america-1906-1914.html

News of the World child labour article with thanks to – https://forum.paradoxplaza.com/forum/index.php?threads/europes-newest-kingdom-a-victoria-ii-belgian-aar-pod.752716/

Child Labour in Britain – http://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/child-labour

Overland Automobile info with thanks to – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Overland_Automobile

G Sommers info with thanks to – http://collections.mnhs.org/MNHistoryMagazine/articles/34/v34i03p106-113.pdf